My home holds a large library filled with antique books, mostly from the mid-1800s, that I’ve collected over the past thirty years. And before you ask—no, I haven’t read them all, but I’m making my way through. The gold-gilded pages, the delicate illustrations, the worn leather spines. Each volume carries a certain weight and dignity. My wooden shelves are lined with the works of Charles Dickens, George Eliot, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, not just for their stories but for the way they were made. These editions feel like artifacts, reminders of a time when books were cherished objects, not just vessels of content.

Much of the collection came from tiny unknown shops, the kind with creaking floors and handwritten price tags. One of my favourite bookshops was The Insatiable Bookstore in Port Townsend, Washington tucked off the main drag beside the automobile museum. I’d spend hours there with the owner, Karen Graham, running my fingers along the shelves, listening to Van Morrison’s Into the Mystic playing on the old record player, selecting one book at a time, building my library.

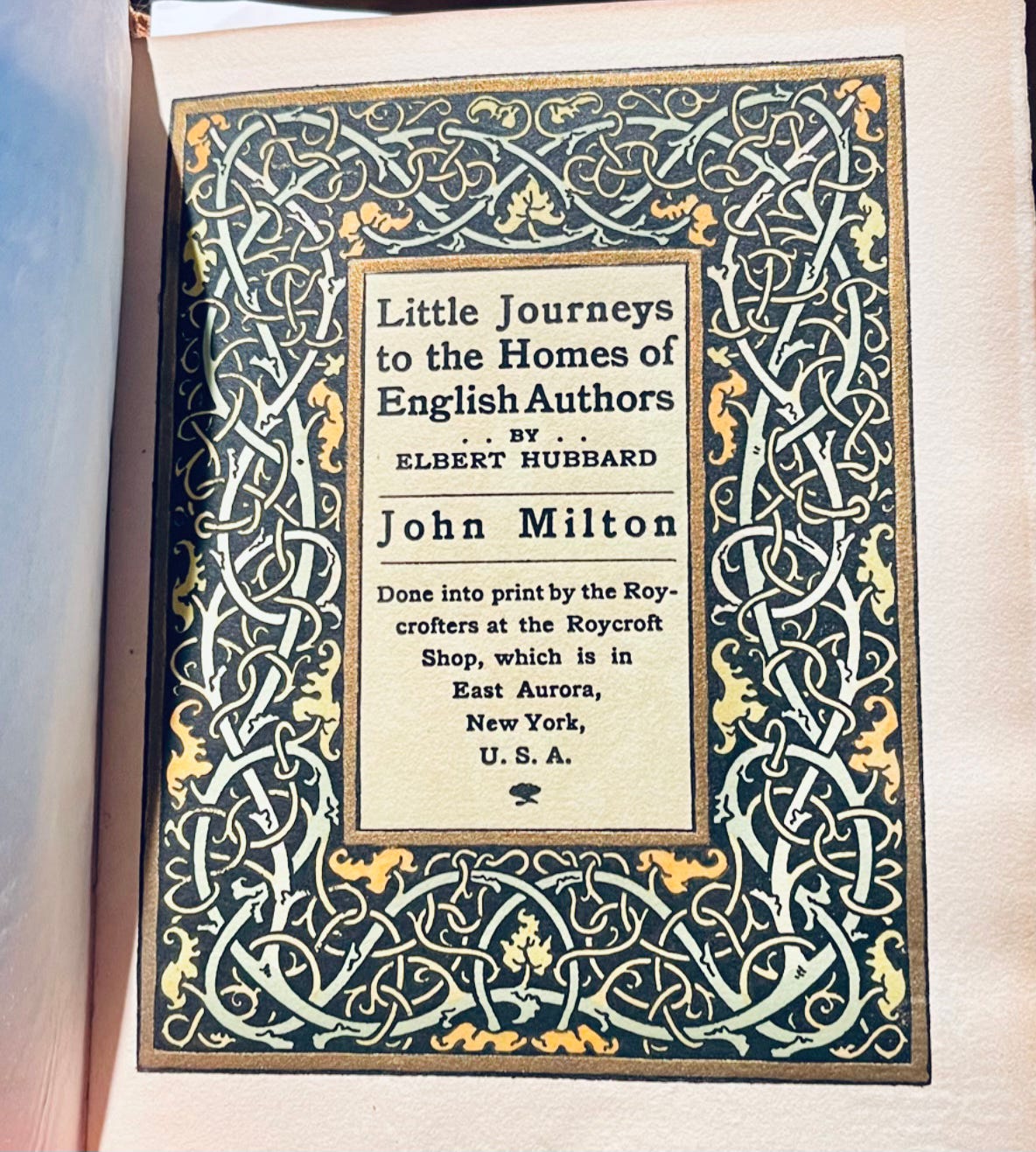

One of my most cherished finds is the complete set of small, hand-bound volumes by Elbert Hubbard from his Little Journeys to the Homes of the Great series. The volume on John Milton, part of the English Authors collection, feels especially sacred to me. These are not just books. They are objects of devotion—pieces of history pressed into paper, ink, and intention.

This particular edition was printed in 1895 by the Roycroft Press in East Aurora, New York, part of a radical arts and crafts movement led by Hubbard himself. He, like me, believed that art belonged in the rhythm of daily life.

The Roycroft movement held that even a book should feel like it was made by hands that cared. And you can feel that care in this one: the weight of the page, the ornate borders, the deliberate typography. Every inch of it whispers that someone paid attention.

This book wasn’t mass-produced. It was typeset by hand, one letter at a time, using movable type. The pages were printed on a hand-operated press by skilled artisans, many of whom lived and worked together on the Roycroft Campus. The intricate border design was likely carved into wood or metal, then inked and pressed onto each page with precision. The paper has a weight and softness that suggests it was made from rag fiber—durable, archival, and meant to last. Even the binding, stitched and assembled by hand, speaks to a slower, more intentional time.

This was something made to be felt as much as read. A book made to endure.

The Roycroft movement embodied a romantic, anti-establishment ethos that rejected the churn of industrial capitalism in favour of craftsmanship, beauty, and intention. For some, it became more than a movement. It was a way of living—almost a spiritual philosophy—rooted in the belief that how something is made matters just as much as what it is. The Roycroft Campus became a haven for printers, furniture makers, metal smiths, bookbinders, and dreamers. It was a collective of artisans who slowed down, paid attention, and made things with care.

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about the importance of attention and care—in my own work, in writing, in poetry, in grief, and in my life.

This came about because this week, I haven’t felt the inspiration to write.

I’ve decided that’s okay. I’m not here to churn out words just to say I did. I’m not going to toss something trivial your way, my friends, simply to feel like I’ve checked off a box.

Instead, I’m learning to honour the pace of my own creativity. To take my time and let inspiration rise when it’s ready.

I’m remembering that slowness is not a flaw—it’s a form of reverence. That the way we make things, the energy we bring to them matters because it becomes part of what they are. So when I do write again, I want it to come from that place. The one where care lives. The one that feels like those hand-bound pages, that someone paid attention to the making.

This week I have been exhaling. My poetry collection, Uprooted: A Season of Grief, is finished. It’s out there now, quietly making its way into the hands and hearts that need it. I trust it’s finding the people it’s meant to find—and that those who need it are discovering it in their own time.

This collection of poems is my way of walking through grief with open hands. I wrote it for my father, and for anyone who has ever loved and lost. It didn’t arrive with a big launch or a spotlight—it’s just me, offering what I’ve made, with the help of a kind editor, a thoughtful cover artist, and the generous readers who have shared it along the way. For that, I’m deeply grateful.

This week I’ve been asking myself, “Where do I go from here? What do I write or create next?”

And the answer is—I really don’t know.

I finished something big. Something soul shifting that came from the deepest parts of me. And now, there’s this strange, open space. It feels hollow but in a good way. It’s the kind of emptiness that asks for rest, that invites reflection, and doesn’t demand answers right away.

So for now, I’m not rushing to fill it. I’m sitting with the not-knowing. Letting the questions breathe. Letting the dust settle around the edges of what was just completed. It feels good.

I believe what comes next will reveal itself when it’s ready to be made.

Until then, I’ll keep tending to the small things—noticing, making notes, experiencing life, and writing when it feels true. I’ll be drinking my coffee slowly, looking for light through the trees, and listening to the world.

That’s where I go from here.

Everything feels better when I remember to slow down and tend to the garden of the making—even the heartbreak, even the joy.

This book by Elbert Hubbard reminds me:

Don’t write something just to get it done.

Make it like it matters.

Because it does.

Make it to feel it.

Make it to remember that you’re here.

Thank you for being here, my friends.

Sincerely,

Mary Ann

If you’d like to hold my poetry collection in your hands, the link to purchase Uprooted is just below. I’m so grateful for every reader it finds.

(If you’ve read Uprooted: A Season of Grief and it resonated with you, please consider leaving a short review on Goodreads or Amazon. Your words help others discover the book—and they truly mean a lot to me.)

References:

Illustration from Little Journeys to the Homes of English Authors: John Milton, Roycroft Press, 1895. Photograph from my personal collection.

As always , refreshing in your pure honesty. Slow and steady wins the race , as my Dad always said.

I love that you are respecting your art, your feelings, and indeed, you are respecting your readers by wanting to share only your best, most heartfelt words and work with them. I like to think I am doing the same. My lack of regularly turning out posts has been bothering me greatly, but because of your words here, I feel like perhaps I need to give myself permission to choose when the time, the words, the thoughts, are worth sharing. Thank you MaryAnn :)